Everything you need to know about Farmland Management

Good farmland management covers a wide range of topics that include improving soil fertility, maintaining water quality, increasing biodiversity and everything in between.

Good farmland management covers a wide range of topics that include improving soil fertility, maintaining water quality, increasing biodiversity and everything in between.

In this guide, you'll learn more about managing your farmland to:

- Get optimal yields with sound grazing management

- Reduce soil erosion and create a healthy soil ecosystem

- Managing water runoffs from the farm

- Establish riparian buffers and increase biodiversity

But first, let’s start with something very important.

Are we asking the right question?

Sustainability is probably one of the most overused words in modern history. Everybody from politicians to economists to armchair philosophers seems to be using it at every given instance.

What's worse?

Today it can mean different things to different people.

But from our narrow vantage point, of farmland management, sustainability simply means being able to go on forever. This definition is both simple and profound. Because you can’t go on forever by depleting the soil, water or pasture quality. So defining sustainable this way makes it clear, concrete and actionable.

With that out of the way, let’s tackle the next big question.

Do we aim to be sustainable, or do we produce more?

On the one hand, researchers and activists claim that livestock farming contributes to more than 6 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions every year and is a major climate change contributor. On the other hand, over the next few decades, the demand for animal products is set to grow by at least by another 50%.

So again, back to our dilemma.

Do livestock farmers produce more?

Or do they aim to reduce their ecological impact?

Both are extreme views. And it’s not a question of this or that. Instead, it’s about accommodating both.

So a better question would be something along the lines of:

How to ensure that our livestock farms and pastures are able to produce optimal yields forever?

After all, that's the goal, right?

But, more often than not, many of us tend to focus more on the immediate results without realizing what’s actually important.

Sure, farm profits and increased production might be our immediate needs. But without long-term fertility, good water reserves or sustainable pastures, the profits and production won’t last for too long.

In other words, good livestock farmers manage a fine balancing act between long-term sustainability and their short-term gains.

Leaning too much towards short-term gains can reduce production and profitability over a period of time. While leaning too much towards long-term sustainability might burn holes in your pocket, without giving you adequate short-term profits. So you’ll want a good mix of both.

For example, when it comes to pasture, native perennial grasses such as bermudagrass, cocksfoot, and crowfoot are all extremely persistent, resilient and nutritious.

Yet they do don’t have high DM per ha yields.

On the other hand, commercial annual ryegrass varieties or legumes such as alfalfa can give you double the dry matter yields but are quite susceptible to pests, diseases and heat stress.

So, you want your pasture to have a mix of both.

For instance, in an ideal scenario, you might have a mix that consists of about 20% to 30% each of: li | native perennial grasses – such as bermudagrass, cocksfoot, and crowfoot li | improved perennial varieties – such as perennial ryegrass li | improved legumes – such as clover, lucerne or alfalfa li | improved annual varieties – such as annual ryegrass or kikuyu

Such a mix will help you have productive pastures across different seasons, weather and moisture availability conditions.

But that’s not all. Grazing plays a huge role in how your pastures perform. That’s next.

1. The Art of Grazing Management

Grazing management is nothing but the art of matching your pasture yields with your animal needs. However, seasons, weather conditions, rainfall (or lack of it) and other such factors can make this anything but simple.

In this section, let’s look at a few important grazing management topics that can help you manage productive and sustainable pastures.

As an experienced grazier, you already know that well-managed pastures are more productive, resilient, persistent and nutritious than poorly managed pastures.

Every grazing management decision counts. Whether it is timing animal movement between paddocks, assessing pasture growth stages or achieving grazing targets.

Every decision has its own set of pros and cons.

For example, leaving your stock in a paddock for too long may help you meet nutrition requirements in the short run, but overgrazing also causes pasture degradation and erosion in the long run. On the other hand, under grazing may give you quicker regrowth but eventually leads to a decline in feed quality.

That’s why good grazing management is an art that is based on scientific principles.

The science behind good grazing management

A grazing cow typically gets 4 to 6 inches of plant material in each mouthful.

When your pasture plants are smaller than this, grazing animals can damage the root systems or even completely uproot the plants.

This is bad because the pasture will take more time to heal and regrow.

On the other hand, when your pasture plants are bigger than 6 inches, a grazing animal only gets the top set of leaves. At the same time, the stem and roots are left intact.

This is good because the plants can use its carbohydrate reserves to quickly regrow new leaves and make more food.

That's why maintaining a post grazing pasture residual of 1,500 kg DM/ ha, or more promotes quicker regrowth and better yields.

But animals need a certain amount of dry matter fodder, every day. That’s why a pre-grazing target of around 3,000 kg DM/ ha or more is recommended.

Because at this level, your animals can eat enough to meet their daily nutritional needs without overgrazing you’re your pasture.

To learn more about how to set your pre and post-grazing targets, read this article on grazing targets.

Rotational Grazing Management and its benefits

Simply put, rotational grazing involves a defined period of grazing followed by a planned period of rest.

The rest period is generally based on how quickly the pasture regrows. As one can imagine, this regrowth depends upon the type of plant species, its growth rate and your weather conditions.

When compared to open or continuous grazing, rotational grazing offers superior benefits in terms of improved nutritional outcomes, dry matter yields, water quality, pasture quality, and soil fertility.

There are several rotational grazing systems. If you’re interested to learn more about them, consider reading our free guide on the different types of rotational grazing systems.

But quickly, here is a list of the ten most widely used rotational grazing systems:

- Time-based rotational grazing

- Herbage-based rotational grazing

- Creep grazing

- Cell grazing

- Strip grazing

- Mob grazing

- Leader-follower grazing

- Rest rotation grazing

- Techno grazing

- Conservation grazing

Each of these ten rotational grazing systems has its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Some offer superior yields but are more expensive and might need more intensive management than other systems. So it’s important to choose a system that works for you and your needs.

Managing seasonal plant growth

The most important thing to realize is that you may not be able to match pasture supply with animal needs throughout the year.

For example, if pasture yields drop in summer, and if you have a summer calving program for beef production, you might have to augment your pasture grazing plans with hay, silage or other concentrated feed sources.

Grazing management is a constant tussle between your local weather, the land's carrying capacity, available resources and your production needs.

Out of these three factors, seasons and local weather has the biggest impact on your grazing plans. Simply, because they are way beyond any human influence.

So the best graziers always work with ebbs and flows of natural seasons.

To better understand this, let’s look at a few broad changes in grazing management, for a cool-temperate pasture across the four seasons.

Autumn:

This is the season where you might have a surplus of pasture growing on your fields. In cool-temperate zones, autumn is when graziers turn their attention towards minimizing pest and disease attacks. To do this, they also closely graze their pasture stands to allow more sunlight and reduce humidity.

Some graziers also might take this opportunity to re-seed and re-establish legumes among their pastures. Depending on their animal needs, graziers also might consider completely resting a few paddocks either to heal, re-establish or to grow surplus hay and silage for winter feeding.

Winter:

This is the season where you might have the least amount of pasture growing in your fields. Cold temperatures do limit the growth of pastures, especially if you are in an area that receives high snowfall.

Graziers tend to treat winter is a period of rest for your pastures. Allowing paddocks a longer rest period compared to other seasons. Some graziers also take this opportunity to plan for the next year. Some also might go one step further and investigate why certain paddocks performed poorly and what interventions are needed.

Spring:

This is the season where you experience maximum plant growth. Spring is when graziers turn their attention towards maintaining a healthy pasture composition of legumes, natives, perennials and high-yielding improved varieties.

This is also when graziers typically follow intensive grazing plans to support their spring calving programs. Pre-grazing targets are typically around 3,000 Kg DM per ha or more. At the same time, post-grazing residual targets are maintained around 1,500 kg DM per ha.

Some experienced graziers may also take this opportunity to completely rest a few paddocks, to manage hay or silage production from them. This helps them reduce feed costs during the upcoming summer, where excessive heat can again limit pasture production.

Summer:

Summers can be hit or miss as far as pastures in cool-temperate climate zones are considered. A good summer with two or three seasonal summer rains can result in a productive pasture growing season. Or at the same time, prolonged heat waves or drought can severely impact summer pasture yields.

Graziers typically turn their attention towards irrigation management and supplemental feeding to overcome pasture shortages during summers. The best ones also ensure that their pastures don’t get overgrazed in summer. Also, summer is the best period for most animal healthcare interventions such as vaccination and worm control programs.

But all said and done. Grazing management is just one part of good land management. In fact, it is incomplete without proper soil fertility and water resource management. Both come next.

2. Managing Soil Fertility

Preventing soil erosion

Most soil scientists agree that it takes around 100 years to make one-inch of fertile topsoil.

Of course, this isn’t a hard number and this time period varies depending on climate, vegetation, and other factors. The point is that it takes very long.

The worst thing that can happen is when this valuable resource gets washed away. Yet, according to historical data, we are losing soil 18 times faster, than it can be built-in nature.

Even worse, overgrazing is the biggest contributor to this loss of topsoil. More importantly, pasture lands that aren’t properly managed can lose anywhere between 0.2 to 0.7 kg of topsoil per hectare every year.

This can be contained to a large extent if you maintain more than 80% of groundcover on your pasture.

Why?

Because plant roots hold the topsoil together and make it less prone to erosion by water or wind.

Groundcover and erosion have a non-linear relationship. With a 40% groundcover, you can lose up to 15 times more topsoil in erosion than when you would lose when you have 80% of groundcover.

In addition to this sound rotational grazing, soil and water management practices can help you turn the tide against soil erosion and build more topsoil instead.

Providing soil nutrients

Healthy pastures are a result of healthy soils. In other words, nutritious pasture derives its nutrients from the soil. In fact, mineral nutrients are the one thing that plants cannot make on their own. They make everything else through photosynthesis. So, your soil has to be rich in nutrients for you to be able to grow nutrient-rich crops and pastures.

Every plant on your pasture accumulates mineral nutrients as it grows. And your animals get these nutrients when they graze on your pastures. So when you look at it that way, it's easy to see why maintaining soil fertility, and nutrients can help you have more healthy and productive animals.

Some sources of mineral nutrients include your farm effluents as well as both organic and inorganic fertilizers. See below picture and note the differences in plant growth under the same conditions of sunlight, soil, container and seed type. However, there’s one difference.

The plants on the left are fertilized while the ones on the right aren’t fertilized.

So, paddocks that are fertilized appropriately will be able to grow better grass with better yields. This, in turn, will help you support higher stocking rates. The increased groundcover will also help you prevent soil erosion and overgrazing.

But over-application of fertilizers can also damage your soil. For instance, excessive use of inorganic fertilizers can make your soil more salty (saline) and kill beneficial soil organisms. In other cases, excessive use of Nitrogen and Phosphorous leads to the pollution of underground and surface water bodies.

Also, beyond a threshold, your plants won’t respond to excessive nutrients. And even worse, you’ll waste money and effort without getting better results.

So how do you know what fertilizers your pasture needs and in what quantities?

The answer is regular soil tests. By doing a soil test every three years or so, you’ll be able to identify key nutrient deficiencies. And create fertilization plans that don’t burn holes in your pocket (or the environment).

For more advice on exact application formulations and optimizing returns on your fertilizer investment – consider talking to old-timers and reputable farm advisors in your region.

Creating a healthy soil ecosystem

But fertilizers have an upper limit. For your pasture to become truly productive, you need to create a healthy soil ecosystem. Healthy soil is home to several bacteria, fungi, protozoa, arthropods, nematodes and other larger soil creatures such as earthworms and beetles. The more diverse the soil organisms, the more healthy the soil ecosystem is.

But all these soil organisms need energy and food to survive and reproduce.

They need lots of organic matter to decompose and get their energy from. That’s why organic carbon content of a soil is a good indicator of how healthy your soil is. Because when there’s food, there’s more life. When there’s little or no food for the soil organisms, there can’t be a thriving soil ecosystem.

The soil life and the organic carbon content together act as a sponge to hold moisture, soil nutrients and energy. They prevent it from escaping the system – either through erosion or leaching. And you can’t get more organic content without plants and trees.

Think of peeling the layers of an onion. The outermost visible layer is that of a productive and profitable livestock farm. But this layer actually sits upon a hidden layer of a well-managed pasture. In turn, the well-managed pasture actually needs healthy soil.

And finally, healthy soils need lots of vegetation to sustain a healthy population of beneficial soil life.

Ideally, you would want your soil organic carbon content to be more than 10%. However, most soils today have much lesser organic carbon content, usually ranging between 2% to 6%. But this is something that can be improved over a few years.

The quickest way to improve your soil health and organic carbon content is to add more compost to it. Alternatively, you can also, over time, add more decaying organic matter directly onto your soils.

Adding your farm animal effluents to the soil directly in appropriate levels can also help you increase your organic carbon content. But by large, the most sustainable way to increase soil organic carbon content is to have more than 75% of groundcover and at least 10% of trees on our farm.

Soil friendly farming practices such as using a seed drill instead of tilling the soil can also help you preserve the soil life and improve soil organic carbon content.

In addition to improving soil fertility, higher levels of soil organic carbon content also greatly increase the water holding capacity of your soil and reduce large scale pest or disease outbreaks.

Next, we’ll look at the relationship between healthy soil and sound water resource management.

3. Managing Water Runoff

As you know, water is the source of life. You need access to clean water if you want to have healthy animals and a productive farm.

So managing water quality is (and should be) a big priority for graziers.

Why?

Because poor quality water can adversely affect the growth, lactation and reproduction in your animals. In other words, improper water resource management will lead to significant economic losses.

A livestock farm can pollute water quality in two ways, through water leaching and runoff. Water leaching is typically not a big problem as long as fertilizers and herbicides are used in recommended dosages. However, excessive use can pollute underground water sources over time.

A bigger and more immediate problem is water runoff. Let’s look at how runoff from livestock farms can pollute water bodies.

How runoff affects water bodies

A livestock farm, by definition, has several farm animals. Through the day, your animal’s poo and pee a lot. Large animals such as beef cattle and dairy cows on average can produce around 50 litres of effluent, every day. In some cases, animals can even produce up to 100 litres of effluents in a day.

These effluents also contain pathogens. To ensure that animals don’t get infected by diseases from these pathogens, farmers wash it away from the animal sheds and store it in a collection pond.

The effluents can sit, ferment and breakdown in these collection ponds for several months. And during heavy rainfall or storm events, this can overflow into the local streams, creeks or rivulets. In turn, they flow into bigger lakes and rivers, before ultimately ending up in our oceans.

In other instances, livestock may have direct access to freshwater streams, ponds or lakes. This means that their urine and feces can directly fall in or near the body of water.

Either way directly or indirectly, livestock effluents end up in water bodies if they aren't managed well. And this is a big problem because it puts a massive strain on our fragile aquatic ecosystems.

Like any ecosystem, freshwater ponds, lakes and rivers have many organisms living in them. Organisms like bacteria, algae, planktons and a variety of fishes – all living in balance with each other. When nutrient-rich effluent or fertilizer runoff enters such an ecosystem, two things happen.

One, the excess Nitrogen and Phosphorus favours the growth of algae and other plants. So a lot of them take over niches that were previously occupied by other more complex organisms such as fish.

And two, as these plants die, while decomposing they'll use up a lot of dissolved oxygen, in turn creating low oxygen conditions that further reduce the population of complex organisms like fish. This is called eutrophication.

After repeated eutrophication cycles, the once clean and clear water bodies that were full of fish turn into greenish algae-filled nutrient-rich water bodies that have no fish. But this is not about fish. Fish is just an indicator of a healthy aquatic ecosystem.

Water that is not purified by a healthy ecosystem is a health hazard for humans and animals. It is also an even greater social and environmental hazard. Ultimately, eutrophication even creates dead zones in oceans.

But things needn’t be this way. Appropriate effluent management can help you prevent this to a large extent. However, during heavy rainfall events, effluents can still escape and enter small creeks, rivulets and lakes in your bioregion. That’s why we need riparian buffer zones.

Preventing runoff with riparian buffers

These buffer zones typically have several layers of trees, shrubs and grasses that are either native or well-adapted to your bioregion. Such a buffer zone offers many ecosystem benefits such as improved organic matter, water percolation and wild habitat. But even more importantly it can help you prevent water runoff from your farm.

As explained earlier, water can carry fertile soil and nutrients away from your farm and create other problems that lead to eutrophication. Even with sound management practices in place, you cannot completely avoid water runoff. Riparian buffers trap soil and nutrient from your runoff in two ways.

Firstly, a dense network of roots and fungi acts like a huge filter to trap soil and nutrients. Secondly, it improves soil structure and allows more water to percolate into the soil. So any runoff water that gets past the riparian buffer zones has very little organic matter or nutrients.

So all in all, locating fenced riparian buffers around water bodies, ponds, creeks and lakes can help you improve soil fertility and also eliminate water runoff related problems.

But why fence the riparian buffer zones?

Because riparian buffers work best with dense vegetation. And you can establish a dense network of trees, shrubs and grasses only when you prevent animals from entering an area. Otherwise, animals will find weak spots and ways to access the water body.

In general, you wouldn’t want to locate riparian buffers very close to the water body for two reasons.

One, because water bodies can flood and occupy a larger area during high rainfall events.

Two, because the sloping land near the banks of a water body is often unstable. Typically, it is advisable to locate your riparian buffer zones at least 10 metres away from the bank of a water body.

But won’t that result in a lot of lost land?

No, because as discussed in an article about trees on your farm, you will actually improve your overall production. Because such a network of trees can help you reduce heat stress effects and also have better natural pest and disease control mechanisms.

That nicely ties into the final section of farmland management.

4. Increasing Biodiversity

More biodiversity means healthier ecosystems. And healthier ecosystems mean more productive soil, pastures and animals.

Greater biodiversity on your farm can offer you many benefits that include:

- nutrient and waste recycling

- shelter for livestock

- sediment control

- flood mitigation

- water storage

- soil formation

- pollination

- pastures and native vegetation

- control of potential pests

- provision of genetic resources

- improved production

Maintaining and improving soil health is the most obvious benefit of all. In addition to this, it can also help you effectively fight against droughts, flooding and even heat stress. For example, well managed native grasses may provide the only remaining forage and groundcover during extended drought conditions.

Lastly, biodiversity also provides natural checks and balances that add stability to your farm enterprise and buffers your pasture from pests as well as disease outbreaks.

In general, we do not consider short-term crops or plants as part of the farm’s biodiversity. Because 3 to 12 months is too short a window of time, for it to have any significant impact on the ecology of your farm. So for all practical purposes, when we talk about biodiversity, we are talking about perennials, shrubs and trees.

Benefits of Perennials

Resilient perennial pasture species are the cornerstones of productive grazing lands. Think of it as the minimum guarantee yield, even when there’s a harsh weather condition such as heatwaves or drought.

Why?

Because their deeper root systems allow them to adapt better to more harsh conditions. They also maintain a groundcover throughout the year. This provides habitat for beneficial soil organisms and also checks soil erosion.

Compared to annuals, perennial pastures can better:

- provide feed outside the growing season

- produce more green leaf in summer

- reduce the supplement feed costs

- provide year-round groundcover

- reduce the risk of soil erosion

- utilize rainfall into a feed

- reduce nitrate leaching

- resist weed invasion

- recycle nutrients

However, they need to be actively managed in the long run. If not properly managed, perennial pastures can quickly degrade within a few years. Prolonged drought, overgrazing and nutrient deficiencies are major factors that can degrade perennial pastures.

On the other hand, good perennial pasture management involves frequent soil testing, rotational grazing and limiting stocking rate.

Benefits of Trees

I’m sure that you’ve noticed how your animals huddle under that single tree on a hot day. Or huddle up against each other when a cold winter wind blows their way.

Why?

Because your animals need to protect themselves from direct heat, dry, hot summer winds and cold winter winds. In a farm context, trees provide this much-needed buffer from the elements.

In addition to this, trees also protect your pasture and crops from heat, cold and high wind speeds. That way, your pasture and crops end up spending lesser energy dealing with harsh elements. Instead, they use this energy to produce more.

That’s why you can actually increase your dry matter yields per hectare when you plant trees on 10% to 15% of your land.

Today, it is well documented that heat stress can lower both milk and meat production in animals. And here are some numbers for you to consider.

Bernabucci et al. (2010) reported that you could lose around 0.27 kilograms of milk, incrementally, with the rise of each temperature-humidity index unit. Similarly, Morignat et al. (2015) observed that heat stress increases, even as little as 1 °C above a particular threshold, increases mortality rates of dairy cows by 5.6% and beef cattle by 4.6%.

Several lines of trees can also help you cut off raging fires and prevent them from causing extensive damage to your farm.

Why?

Because fires can only use dry material as fuel.

And finally, trees can help you effectively deal with those messy, wet and slushy parts of your farm. That is if you carefully select water-logging tolerant tree species. Over time, the shelterbelts will improve your soil structure, add more carbon and percolate down a significant amount of excess water.

You could incorporate trees on your farm in several ways. You could use them to complement your pasture and crops in riparian buffer zones, shelterbelts and windbreaks.

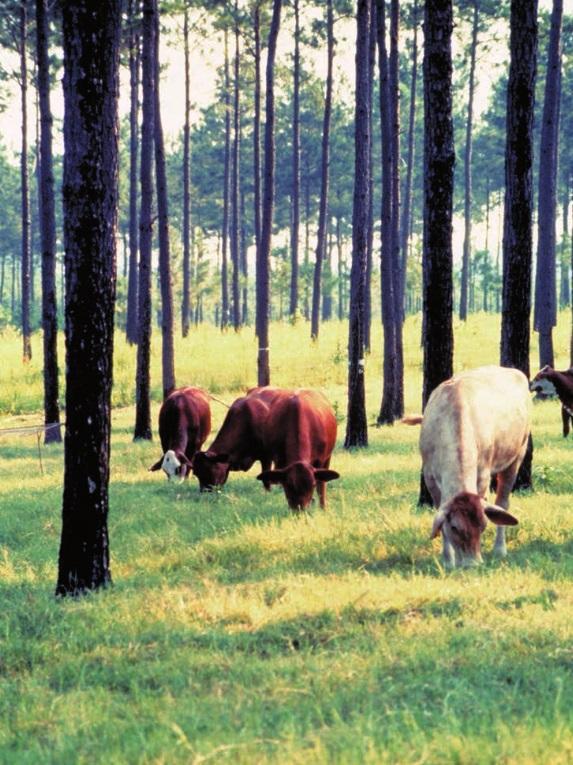

Or you can take this one step further and consider integrating trees along with your production systems through alley cropping, silvopasture or agroforestry production practices.

Either way, think of trees as your long-term investment. Something that can help you save all the progress you've made on your farm in terms of improved pasture production and soil fertility. Something that can help you deliver these benefits on to the next generation.