Australian dairy farmers lose more than $150 million every year due to poor udder health. And Mastitis is the main cause of this loss.

Mastitis is a disease that reduces both milk production and quality. It is a complicated and costly problem. And there are no simple solutions. But you can still prevent and treat Mastitis to a large extent.

Here are a set of best practices of what you can do, why you should and how you can control mastitis from spreading in your dairy herds.

What is Mastitis and how does it spread?

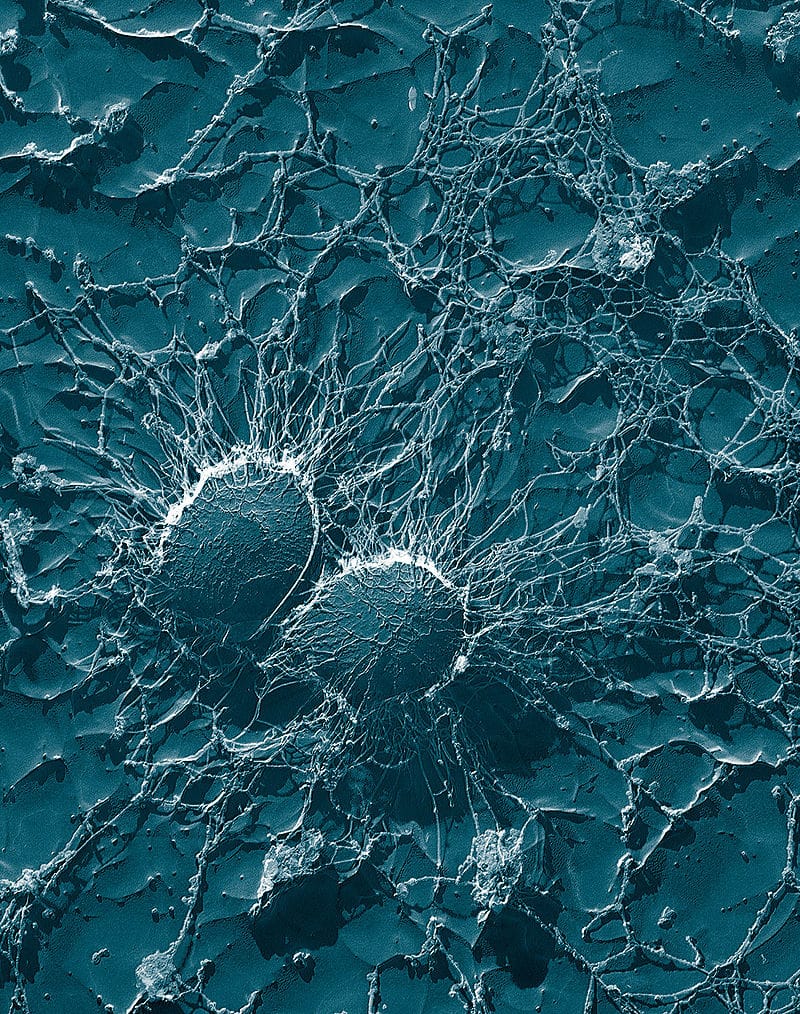

Mastitis is a bacterial infection of the mammary glands in cows, that enter via the teat and multiply in the udder, causing inflammation.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common strain of bacteria that causes mastitis in cows.

Streptococcus agalactiae is the other strain.

Mastitis spreads in two ways:

- contagious mastitis – that spread from other infected cows and

- environmental mastitis – that spread from bacteria found in the surrounding soil, manure, bedding, water etc.

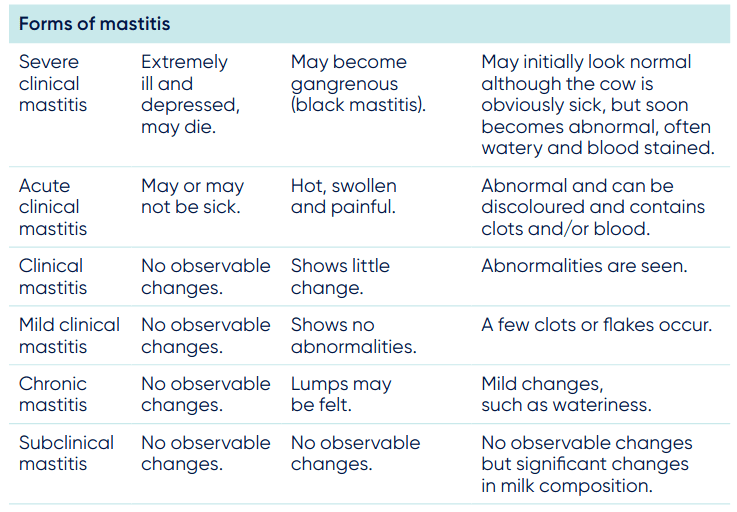

Clinical mastitis are infections that exhibit visible symptoms such as udder swelling or redness while subclinical mastitis doesn’t cause visible changes in milk or udder appearance, and is harder to detect.

Why control mastitis?

Because Mastitis reduces milk production and profits.

Long term infections in your herd damage milk secretory cells, result in lower milk yields. And in turn will result in lower profits.

That’s why Mastitis is also known as one of the costliest diseases that can affect dairy herds.

In addition to this, it can also cause significant pain and discomfort to your cows.

What happens behind the scenes of a mastitis infection?

When a cow gets infected with mastitis, it’s immune system sends white blood cells to the udder to fight the mastitis bacteria.

About 2% of these body cells (called somatic cells) are shed into the milk from the udder.

This concentration of body cells in milk is called its cell count. When you take a milk sample from all four quarters of a cow, it is called an Individual Cow Cell Count (ICCC) or Somatic Cell Count (SCC).

SCC rises significantly when a cow is infected with mastitis.

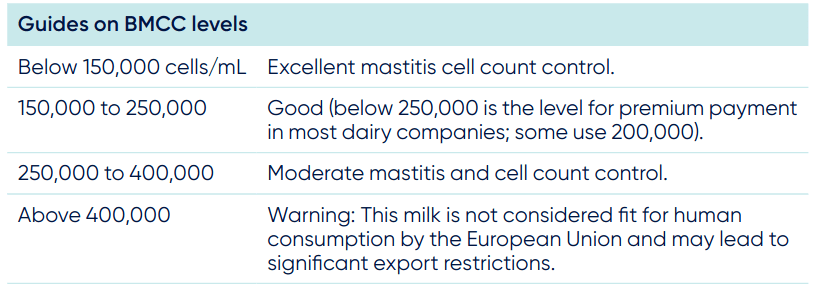

The concentration of cow body cells in milk from all cows in your herd, that goes into the vat is called a Bulk Milk Cell Count (BMCC) and estimates subclinical mastitis in the herd. A series of vat samples should be collected through the drip sample taken when you empty the vat.

Each 100,000 cells/mL points to about 10% of infected cows are infected.

If your herd has BMCCs below 200,000, and you see a sudden increase, you might have a clinical case of mastitis infection in one or more cows. It needs your immediate attention.

Prevention and Control of mastittis:

The two basic factors in controlling mastitis or intramammary infections (IMIs) are minimizing (a) the rate of new infections and (b) the duration of infections already present.

The rate of new intramammary infections is related to a number of variables due to exposure of the teat end to mastitis-causing pathogens.

These potential pathogens can be found in the cow’s environment, inside milking unit liners, colonizing or contaminating normal teat skin (especially near the orifice), or in colonized or infected teat skin lesions, e.g. abrasions, wounds, or fly bites.

Disinfecting teats immediately after every milking kills most pathogens on the teats.

It also can help heal the lesions and infected skin condition. And in turn may prevent more pathogens from entering the mammary gland.

Provide a low stress environment:

It's inportant to provide a Low Stress Environment for your cows and heifers.

Oxytocin is the milk ‘let-down’ hormone produced in the cow’s brain in response to the stimulus of her calf sucking, or the anticipation of milking.

When cows are anxious or uncomfortable, the let-down response is suppressed, decreasing milk flow.

Stress can occur due to various reasons like unusual sounds, unknown people in the milking area, pain due to improper milking machine or due to mastitis, non-routine udder or milking procedures, and even harsh treatment of forced movement of cows.

Clean stalls and bedding:

Ensure you have clean stalls, dry and comfortable bedding for your cows. Anything less will suppress their milk production and make them prone to contracting mastitis. You should evaluate cleanliness and dryness by observing the udder and rear quarters.

Foremilk and Udder check:

You have to ensure a consistent routine and a calm milking environment, to prevent predisposing your cows to the risk of mastitis.

Before milking, inspect the teats and four quarters in detail. Do not milk chapped, cracked or bleeding teats or teat ends, they are predisposed to new infections.

‘Stripping’ is when you remove three or four streams of milk from each teat before milking.

You can spot the quarters that have been infected with mastitis at stripping, by palpating the udder regions for swelling or hardness or looking for redness.

Always use a strip cup or plate, collect milk and discard them into the drains to prevent bacterial spread in the milk parlors. You should clean and sanitize the strip cups after each milking.

If you are stripping milk onto the floor, avoid splash back to udders and do not strip milk onto hand or gloves as bacteria may spread to other cows.

Disinfecting teats:

- Wash Teats with an Udder Wash Solution or Predip Teats in an Effective Disinfectant Product

- Cover only teats while applying disinfectant via hose (not the whole udder, as any dripping solution can transfer bacteria to teats and cause elevated bacteria counts in bulk tank milk

- Ensure sprinkler pen heads are working and adjusted for the amount of dirt and manure to be cleaned

- Ensure udders are dry before entering the milking parlor, and you should use towels (hand towels or paper towels) only once to dry the udder and teats.

- Risks of mastitis increases and milk quality decreases if you milk wet teats. Because chapping, pinching or bleeding occurs when teats are not completely dried, making cows susceptible to bacteria. So dry off all quarters in all cows using a dry cow treatment product

Attaching the milking unit:

You must attach the milking machine within 60 to 120 seconds after prepping, so that maximum milk can be harvested at the time of hormonal release and milk let-down.

Whether you milk the cows from the side or between the rear legs, you have to carefully attach the unit and not let excess air enter the milking system via teat cups.

Most cows can milk out in four or eight minutes. Once attached, pay immediate attention to slipping or squawking of teat cups, as slipping of teat cup liner can irritate the teat and block milk flow.

Also, it is proved that most of the new mastitis infections are caused by liner slips during milking. You should leave alone quarters that do not get milked out completely, until the next milking.

Removing teat cups:

The method you would use to remove teat cups just when the last quarter in milking out, is more important than timing of removal. You should always shut off the vacuum before removing teat cups, and not pull them out under vacuum, as it causes linear slip and new infection in another quarter.

Disinfecting teat cups after removal:

Immediately after milking, cover the entire teat in disinfectant to kill all bacteria.

There are several effective teat dip products in the market that can reduce new infections by upto 60%.

Also ensure your teat cups are always kept sanitized, discarding any contaminated dips. There are weather specific formulations that protect teat skin from freezing during winter. You also have options of using teat sprays or foams.

At all times you have to keep the teat disinfectant off the floor and away from back splash while milking.

Other management factors:

- Remove udder hair periodically (every 3 months) to reduce dirt and manure that can stick there and to lessen the dry off time

- Milk first lactation cows first, the second or later lactation cows with low SCC next and cows with high SCC third, keeping the mastitis infected cows for the last milking spot. The order in you milk the cows can help contain spread of mastitis from cow to cow

- Periodically change and disinfect your milking gloves to reduce new infection

Treatment of clinical cases:

You can detect clinical mastitis early with a strip cup and also use the Californian Mastitis Test (CMT) to confirm.

The CMT also called RMT (Rapid Mastitis Test), is a ‘cow-side’ test that instantly detects subclinical mastitis by estimating the cell count of the milk and categorizing into one of five scores, depending on the gel reaction when a reagent is added to the milk.

You can carry out the test at milking, by squirting a small quantity of sample milk from each quarter into separate dishes and an adding an equal amount of reagent to each.

When you swirl the milk and reagent, you will see the extent the gel has solidified (none or almost solidified) that scores the infection.

Once infection has been detected in the udder, you can choose from four ways to eliminate the disease: spontaneous cure, the culling of chronically infected cows, treatment during lactation, and dry cow therapy.

However, antibiotic treatment is the most effective method to eliminate mastitis.

In recent times, selective antibiotic dry cow therapy is being favoured, when the SCC is less than 200,000/ml. Only the infected quarter(s) are treated with drug infusion.

Culling chronic, non-responding cows is a positive effort in mastitis control, and is a practical way for you to to eliminate chronic infections that do not respond to repeated treatment attempts, especially if the agent involved is staph.

All said and done, you, as the herd manager need to decide on the correct mastitis treatment approach to adopt in your dairy farm. Because you are expected to balance cure rates, the production at stake and the risk of antibiotic resistance – all at the same time.

If required, do consult with your vet and farm advisor about different possible courses of action.

That brings us to the end of this article. We hope you found this useful. Until we meet again, happy farming.

- The Dedicated Team of Pasture.io, 2020-12-28